The Removal of Native Children

If you keep up with current Indigenous news, you most likely have come across the topic of Native adoption. It’s an issue that inspires a lot of emotion and trauma amongst most tribes in the United States and elsewhere. But what is it? And why is it important for both Native and non-Native people to understand? We’re here to fill you in and point you in the right direction for learning more.

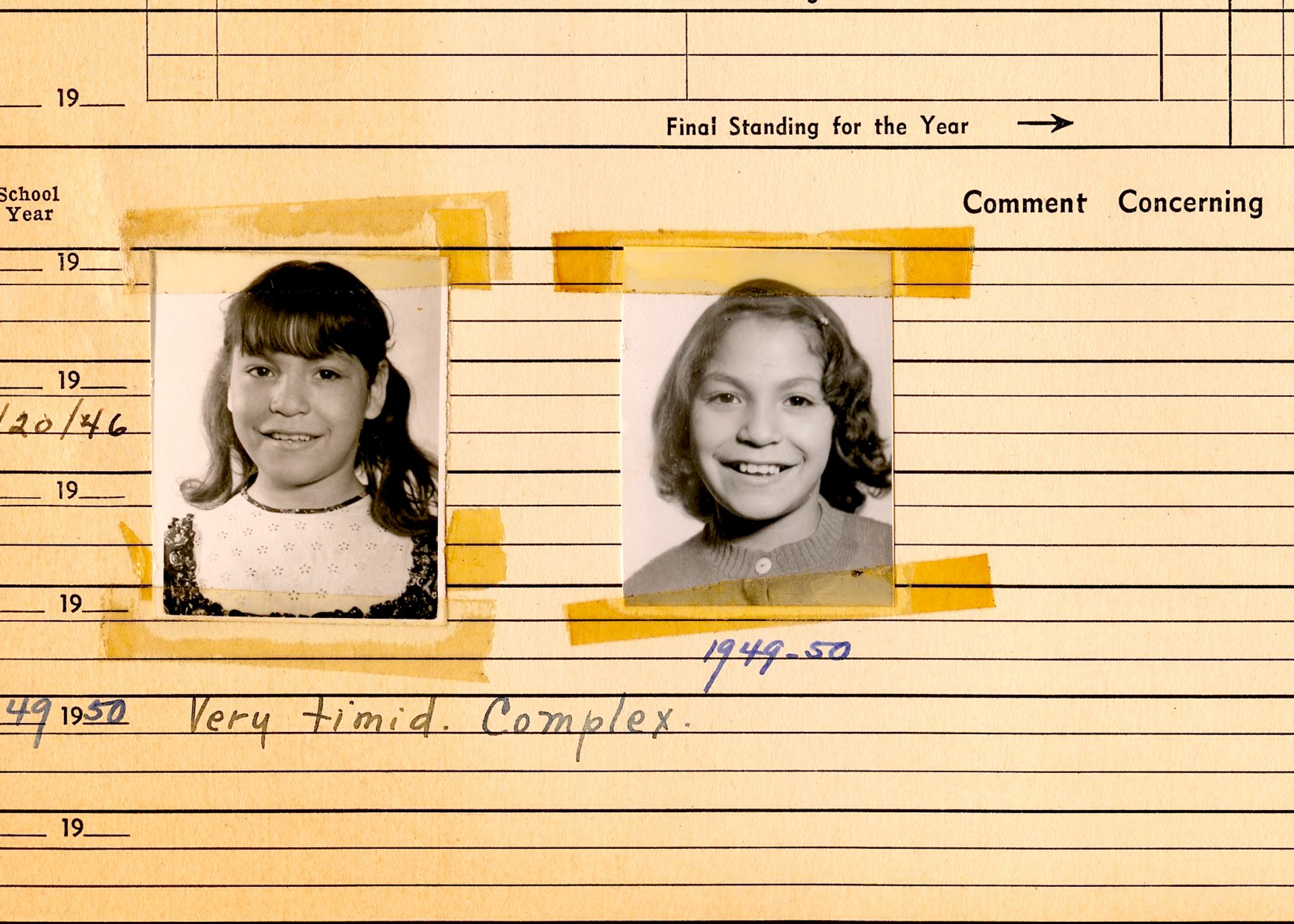

Although many have heard of the horrors and abuse of Native children forced into boarding schools, many are not aware of The Indian Adoption Project, a federally recognized program that removed almost a third of Native children from their homes and tribes from 1958 to 1967 as stated by an article by Indian Country Today.

According to Britannica.com, before the 20th Century, the majority of models of well-being used by child welfare services reflected the culture of the Euro-American middle class. Most often this model included a father who worked outside the home, a stay-at-home mother, and a residence with material conveniences such as electricity. These expectations stood in contrast to the values of reservation life, which held a more community-based approach to family life and wealth. As a result, a disproportionate amount of Native children were removed from their homes and into non-Native households, effectively erasing yet another Native generation.

The National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA) stated that “research found that 25%–35% of all Native children were being removed from their families. Of these removals, 85% of Native children were placed outside of their families and communities—even when fit and willing relatives were available.”

Native children taken out of their homes and forced to assimilate according to Euro-American culture still devastates generations of Native people today. In many cases, the adopted children were reprimanded for their culture and appearance and completely removed from their heritage. An article by Indian Country Today gives many first-hand accounts of the trauma experienced by Native adoptees. Many Native adoption survivors report a feeling a loss of self due to being raised away from their culture, and in some cases, there are reports of being placed in abusive homes.

What is ICWA?

The National Indian Children Welfare Association (NICWA) states the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) was passed in 1978 to help protect Native American parents from “involuntary removal” of Indian children in response to an alarming amount of child removals from Native American families. The law was designed to keep Native families together and protect their children from having their lives determined by non-Native organizations, and for the most part, it’s been widely successful. To learn more about the specifics behind ICWA, we recommend you visit NICWA’s website: https://www.nicwa.org/about-icwa/

Adoptive Couple v. Baby Girl (Baby Veronica)

One of the most well-known and controversial cases of Native adoption revolves around Veronica, better known as Baby Veronica. According to an article by The Atlantic published in 2013, Veronica is the daughter of Dusten Brown (Cherokee) and Christina Maldonado. Prior to her birth, Veronica’s mother arranged for her adoption without telling the father, and once she was born, she was sent home with a non-Native adoptive couple.

Months later, when Veronica’s birth father discovered this information, he set out to block the adoption and gain custody. Some argued his case fell under ICWA. However, Veronica’s adoptive parents fought his claim, stating Brown had waived his rights.

According to an article by NPR, after a long legal battle, Veronica’s father finally ended his fight to protect his daughter from the media, and the girl was returned to the adoptive couple.

Although this case is the most well-known, the circumstances behind the “Baby Veronica” case are not uncommon.

The Future of Native Adoption & Foster Care

There are several organizations working to improve the adoption and foster care system for Native Children, but the National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA) is the most comprehensive source of information on child welfare. They work to keep Native families together through education of families, policy makers, case workers, and tribal communities. NICWA also advocates for compliance of ICWA and defends it against attacks from those wishing to overturn it. According to NICWA, even today “Native families are four times more likely to have their children removed and placed in foster care than their White counterparts.” Understanding why it’s important to keep Native children connected to their culture and families and recognizing the policies in place that keep them there is one of the biggest steps in overcoming this disparity.

To learn more about their resources visit https://www.nicwa.org/.

Films about Native Adoption

Survivors of Native adoption are coming together to share stories and heal with their communities. Storytelling has become an essential tool for both education and healing. We invite you to watch our latest films on survivors of Native adoption.

Blood Memory

Battles over blood quantum and ‘best interests’ resurface the untold history of America’s Indian Adoption Era – a time when nearly one-third of children were removed from tribal communities nationwide. As political scrutiny over Indian child welfare intensifies, an adoption survivor helps others find their way home through song and ceremony.

Dawnland

For decades, child welfare authorities have been removing Native American children from their homes. In Maine, the first official “truth and reconciliation commission” in the United States begins a historic investigation. DAWNLAND goes behind-the-scenes as this historic body grapples with difficult truths, redefines reconciliation, and charts a new course for state and tribal relations.

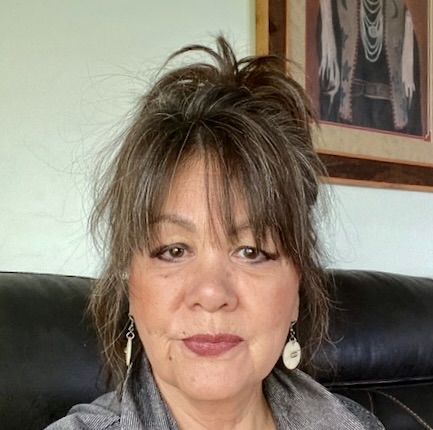

Daughter of a Lost Bird (not yet released)

What does blood have to do with identity? Kendra Mylnechuk, an adult Native adoptee, born in 1980 at the cusp of the enactment of the Indian Child Welfare Act, is on a journey to reconnect with her birth family and discover her Lummi heritage.